Anyone with a driver’s licence will be familiar with the scanners. At the entrance to almost every office park, medical facility, retirement home or private estate, security guards equipped with scanners will ask to scan your driver’s licence. It serves as a replacement for the old sign-in book and is so prevalent that it has become the norm, but should drivers simply be handing over their cards without a second thought?

It turns out that the barcodes on a driver’s licence contain far more information than should be handed to a security company without a second thought and when combined with a quick scan of the vehicle registration can give the security company a startling amount of information that the unscrupulous could use for any number of crimes, including eNatis fraud, where vehicles are transferred out of a person’s name or cloned, without their permission or knowledge.

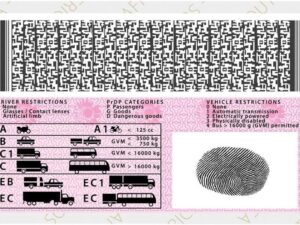

According to the companies that build the scanners they do little more than copy the information visible on the surface of the card, which includes a photograph, full name, identity number, date of birth, driving licence restrictions, gender, and South African citizenship status. The truth is a lot more nuanced.

What can scanners detect?

Scanner developers make their scanners by purchasing decryption licences from South Africa’s Electronic National Administration Traffic Information System, or eNatis. This allows them full access to the information encrypted on the eNatis barcode system, which includes a lot more information than a simple copy of the licence. In order to gain a driver’s licence users need to hand eNatis a lot more information, including their residential and business addresses, telephone numbers, and other contacts including email, which are included. Fortunately, more recent versions of the barcode do not include the signature and thumb print.

The worst part of all of this is that the scanner records those details to an unknown server, with security and protections, which are likely not up to scratch. According to inside sources, many scanner companies allow security firms to have multiple logins to the data without auditing, as well as the compiling, sending and emailing of reports including clients’ details. Some also allow the guards themselves to see information that is not relevant to their work.

While there are some scanners that do their best to protect the information they now have on hand, the vast majority do not, and there are many who argue most of these scanners and the circumstances under which they collect and store information are in direct violation of the POPI act.

Technically, companies, estates, and facilities that do not protect the information they gather adequately could now be challenged on POPI and administrative fines may be levied by the regulator. Asking around, however, it seems very few have the will to protect their information to that degree. So for now, drivers and security companies exist in an uneasy stalemate, one that only serves to help the security firms.